NOTE:VIDEO AT THE END OF ARTICLE.

Introduction

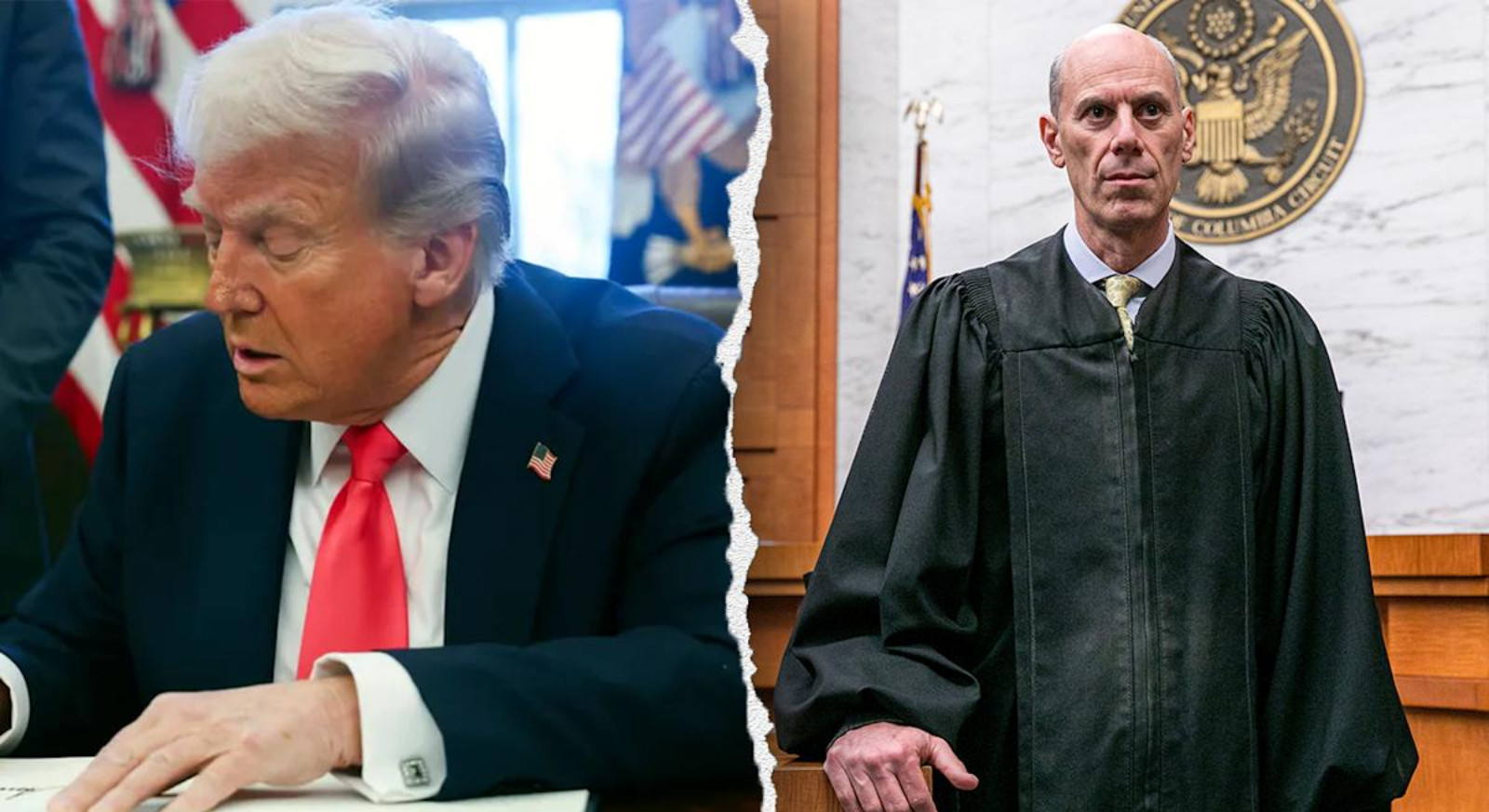

In a decision that has reverberated throughout conservative legal and political circles, U.S. District Judge James Boasberg granted a temporary restraining order blocking President Donald J. Trump’s recent deportation directive under the Alien Enemies Act. The order, issued last week, prevents the administration from removing Venezuelan nationals whom the President had designated as members of a foreign terrorist organization. Conservatives have condemned the ruling as an unprecedented judicial encroachment on executive authority. Prominent commentators and Republican lawmakers alike are warning that the decision—if allowed to stand—would fundamentally alter the balance of powers enshrined in the Constitution and severely constrain the President’s ability to address national security threats.

This article examines the facts of the case, unpacks the legal and historical underpinnings of the Alien Enemies Act, analyzes the relevant Supreme Court precedent, and considers the broader institutional and policy implications of Judge Boasberg’s injunction. We also explore the chorus of conservative criticism, including calls for impeachment of the judge, and assess the potential paths forward, from appellate review to possible Supreme Court intervention.

1. The Trump Administration’s Use of the Alien Enemies Act

1.1 Presidential Directive and Targeted Population

In early April 2025, President Trump issued an executive order invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to authorize the arrest and removal of certain Venezuelan nationals residing in the United States without lawful status. The order specifically targeted individuals whom the administration identified—through Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Department of Justice (DOJ) intelligence—as members or associates of a violent criminal organization with ties to Venezuelan political factions designated as terrorist entities under federal law.

The stated rationale was twofold: first, to safeguard American communities from criminal actors operating transnational networks that facilitate narcotics trafficking and violent crime; second, to send a clear deterrent signal to foreign adversaries who exploit U.S. territory as a safe haven. Administration officials argued that standard immigration removal proceedings were both too slow and too lenient to protect the public from this group’s alleged illicit activities.

1.2 Emergency Injunction by Judge Boasberg

On April 10, 2025, Judge Boasberg granted a nationwide temporary restraining order (TRO) halting all deportations under the President’s directive. In his 22‑page opinion, the judge raised concerns about due‑process violations, questioned the legality of bypassing Article III judicial review, and flagged potential overbreadth in the administration’s designation criteria. Although the full memorandum remains under seal pending appeal, public reports indicate that Boasberg emphasized two central points:

- Limited Judicial Nonreviewability: Contrary to the White House’s argument that the Alien Enemies Act confers absolute nonreviewable authority on the President, Boasberg concluded that the statute’s text does not categorically preclude judicial oversight, especially when removals implicate fundamental constitutional protections.

- Procedural Safeguards: The judge noted that the administration had provided minimal notice and no meaningful opportunity for affected individuals to contest the designation before removal, raising serious due‑process concerns under the Fifth Amendment.

By issuing the TRO, Boasberg effectively paused the deportation operation for at least 14 days—the maximum duration for such an order without a full evidentiary hearing—thus giving petitioners time to seek a preliminary injunction and further judicial review.

2. Conservative Backlash: “Troubling” and “Defying Precedent”

2.1 Greg Jarrett’s Criticism

Fox News legal analyst Greg Jarrett was among the most vocal critics of Boasberg’s ruling. In a segment on April 12, Jarrett denounced the decision as a brazen defiance of Supreme Court precedent. He underscored the 1948 case Ludecke v. Watkins, in which the Court upheld President Harry Truman’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act during World War II and held that such presidential orders were not subject to judicial review:

“What’s so troubling about Boasberg’s restraining order is that he is defying the Supreme Court, which reviewed Harry Truman’s use of the Alien Enemies Act after World War II ended,” Jarrett argued. “The high court said that not only is the Act constitutional, it is not subject to judicial review by any judge.”

Jarrett contended that by issuing a TRO, Boasberg arrogated unto himself the very power that Ludecke disallowed. He warned that if lower‑court judges could second‑guess the President’s national‑security determinations under the Alien Enemies Act, the result would be unworkable legal chaos and a crippling of the executive branch’s ability to respond swiftly to emergent threats.

2.2 Calls for Impeachment and Official Rebuke

Following Jarrett’s segment, a handful of conservative commentators and Republican lawmakers publicly urged disciplinary action against Judge Boasberg, with some even hinting at impeachment for alleged misconduct in office. Representative Elise Stefanik (R‑NY) wrote on social media that the judge had “overstepped his authority and must be held accountable,” while Sen. Ted Cruz (R‑TX) described the ruling as “judicial activism of the worst kind.”

However, constitutional scholars caution that impeachment of a federal judge requires proof of high crimes or misdemeanors—not mere disagreement with a legal ruling. Federal judges enjoy life tenure precisely to insulate them from political pressure when interpreting the law. Nonetheless, the intensity of the conservative outcry underscores the broader political stakes at play.

3. Legal Foundations of the Alien Enemies Act

3.1 Enactment in 1798

The Alien Enemies Act was part of the broader Alien and Sedition Acts enacted by the Federalist-dominated Congress in 1798. Designed to address fears of French invasion and subversion during the Quasi‑War with France, the Act authorizes the President, “whenever the United States shall be at war” with a foreign power, to detain and remove non‑citizens who are nationals of that power. The statute’s language grants the executive “the exclusive power . . . to order the removal of all enemy aliens” and explicitly contemplates broad presidential discretion.

3.2 Post‑World War II Usage and Ludecke v. Watkins

Although the Act predates the Constitution’s ratification of the Bill of Rights, it survived subsequent legal challenges. In 1948’s Ludecke v. Watkins, the Supreme Court considered whether President Truman had the authority under the Act to deport German‑national residents, some of whom alleged they had become naturalized U.S. citizens. The Court upheld Truman’s removals and emphasized that:

“The very nature of the President’s power to order removal of all enemy aliens rejects the notion that courts may pass judgment upon the exercise of his discretion.”

By invoking the political‑question doctrine, the Court concluded that the Alien Enemies Act “precludes judicial review of the removal order.”

4. Judicial Review and the Political‑Question Doctrine

4.1 Scope of Nonreviewability

The political‑question doctrine holds that certain matters fall exclusively within the purview of the political branches—namely, the executive and legislature—and are therefore nonjusticiable. While Ludecke affirmed that wartime alien‑enemy removals are largely immune from judicial second‑guessing, subsequent rulings have allowed limited review of statutory interpretation and procedural compliance.

4.2 Procedural Due Process Under the Fifth Amendment

Even where the executive enjoys broad discretion, individuals facing government action may assert Fifth Amendment due‑process claims if the action deprives them of “life, liberty, or property” without adequate notice and hearing. Courts have split on whether the statutory text or historical practice requires a pre‑removal hearing in non‑emergency contexts. Boasberg’s TRO suggests that he found the administration’s process insufficient to satisfy constitutional minima, notwithstanding Ludecke’s broad nonreviewability holding.

5. Analysis of Judge Boasberg’s Ruling

5.1 Textual Interpretation of the Statute

Reports indicate that Boasberg conducted a close textual analysis of the Alien Enemies Act, concluding that while the President enjoys substantial discretion over removal determinations, the Act does not categorically bar judicial inquiry into whether the statutory criteria have been met. In particular, the judge appeared to interpret the phrase “all enemy aliens” as subject to core components of administrative‑law review—requiring at least a plausible factual basis for designation, even if the standard is deferential.

5.2 Due‑Process Considerations

Boasberg reportedly took issue with the lack of individualized process: the administration did not provide affected individuals with written notice of their enemy‑alien status, evidence supporting the designation, or an opportunity to respond before the government initiated removal proceedings. The judge suggested that, in light of modern constitutional requirements, the framers could not have intended to strip all judicial safeguards from noncitizens facing exile.

5.3 Balance of Hardships and Public Interest

In granting a TRO, a court must weigh the movant’s likelihood of success on the merits, the balance of equities, and the public interest. Boasberg’s order implies that he found serious questions as to the lawfulness of the President’s actions and concluded that the public interest in safeguarding constitutional rights outweighed any urgency in executing the deportations.

6. Conservative Counterarguments

6.1 Executive Prerogative in National Security

Proponents of Boasberg’s reversal, including Jarrett, insist that national security and foreign‑policy decisions historically reside with the President and Congress, not the judiciary. They point to the Framers’ delegation of war powers to the executive, as well as centuries of U.S. precedent affirming broad emergency authority.

6.2 Risk of Judicial Micromanagement

Critics warn that if lower courts may enjoin deportations under the Alien Enemies Act, litigants will flood the judiciary with challenges, leading to a patchwork of conflicting injunctions. They argue that uniform, swift action is essential to counter threats from transnational criminal networks labeled as terrorist organizations by the executive branch.

7. Implications for Immigration Policy and Constitutional Order

7.1 Impact on Current and Future Administrations

If Boasberg’s reasoning prevails on appeal, subsequent administrations—regardless of party—may face increased judicial scrutiny before effectuating rapid removals under the Act. This could slow executive responses to emergent national‑security crises and require formal notice‑and‑hearing procedures in courts across the country.

7.2 Separation of Powers and Institutional Legitimacy

The case raises fundamental questions about the separation of powers. By asserting the authority to enjoin a presidential directive made under a centuries‑old statute, the judiciary reaffirms its role as a check on executive power—but risks accusations of overreach. Conversely, an absolutist reading of nonreviewability could marginalize the courts and leave no remedy for government abuses.

8. Path Forward: Appeals and Potential Supreme Court Review

8.1 Appeal to the D.C. Circuit

The Justice Department has already filed an emergency motion with the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals seeking to dissolve Boasberg’s TRO and reinstate the deportations. Given the D.C. Circuit’s historical deference to executive prerogative in national‑security matters, the panel may stay the TRO pending full briefing on the merits.

8.2 Possible Supreme Court Intervention

Should the D.C. Circuit affirm Boasberg’s ruling or split 2–1, the administration is likely to seek certiorari from the Supreme Court. The Justices would then have to decide whether Ludecke’s nonreviewability holding remains good law in the modern administrative‑state context, and how due‑process protections apply to noncitizens designated under the Alien Enemies Act. With the current ideological balance on the Court, a close decision is possible, potentially reshaping the scope of executive authority in wartime and national‑security scenarios.

9. Conclusion

Judge Boasberg’s decision to enjoin President Trump’s deportation order under the Alien Enemies Act has ignited a fierce debate over the proper roles of the judiciary and the executive in safeguarding the nation. Conservative critics decry the ruling as a flagrant defiance of Supreme Court precedent and a perilous expansion of judicial power. They warn that subjecting enemy‑alien removals to pre‑removal hearings and judicial oversight will undercut the President’s constitutional responsibility to defend the republic.

At the same time, defenders of Boasberg’s order emphasize the enduring necessity of judicial safeguards—and of due‑process protections—whenever government action threatens to extinguish liberty or exile individuals from our shores. The ultimate resolution of this dispute, whether in the D.C. Circuit or before the Supreme Court, promises to clarify—or recast—the contours of executive discretion under one of our oldest statutes and to define anew the boundaries of judicial review in matters of war, terrorism, and immigration. The final outcome will have lasting implications for constitutional law, national‑security policy, and the balance of power among America’s three coequal branches of government.